The prevailing anxiety in Western capitals these days concerns Beijing’s ascendancy in artificial intelligence. The fear is palpable: If China leads in AI, it will dominate the 21st century. Yet, this geopolitical obsession often obscures a more pedestrian, immediate reality. We already inhabit a digital cosmopolis defined by borderless utility. We use Google and Meta for search and connection; we use TikTok for entertainment. The eventual adoption of non-Western foundational models—like the emerging Chinese contenders DeepSeek or Yi—seems not a question of if, but when.

Adopting a tool, however, is not the same as adopting an ideology. The everyday use of Chinese algorithms does not presage a mass conversion of Westerners to Chinese citizenship, nor does it necessarily signal Beijing’s imminent intent to seize planetary control. The military and social implications of a fragmented AI landscape are real, certainly, but they require adaptation and evolution, not paralyzed panic.

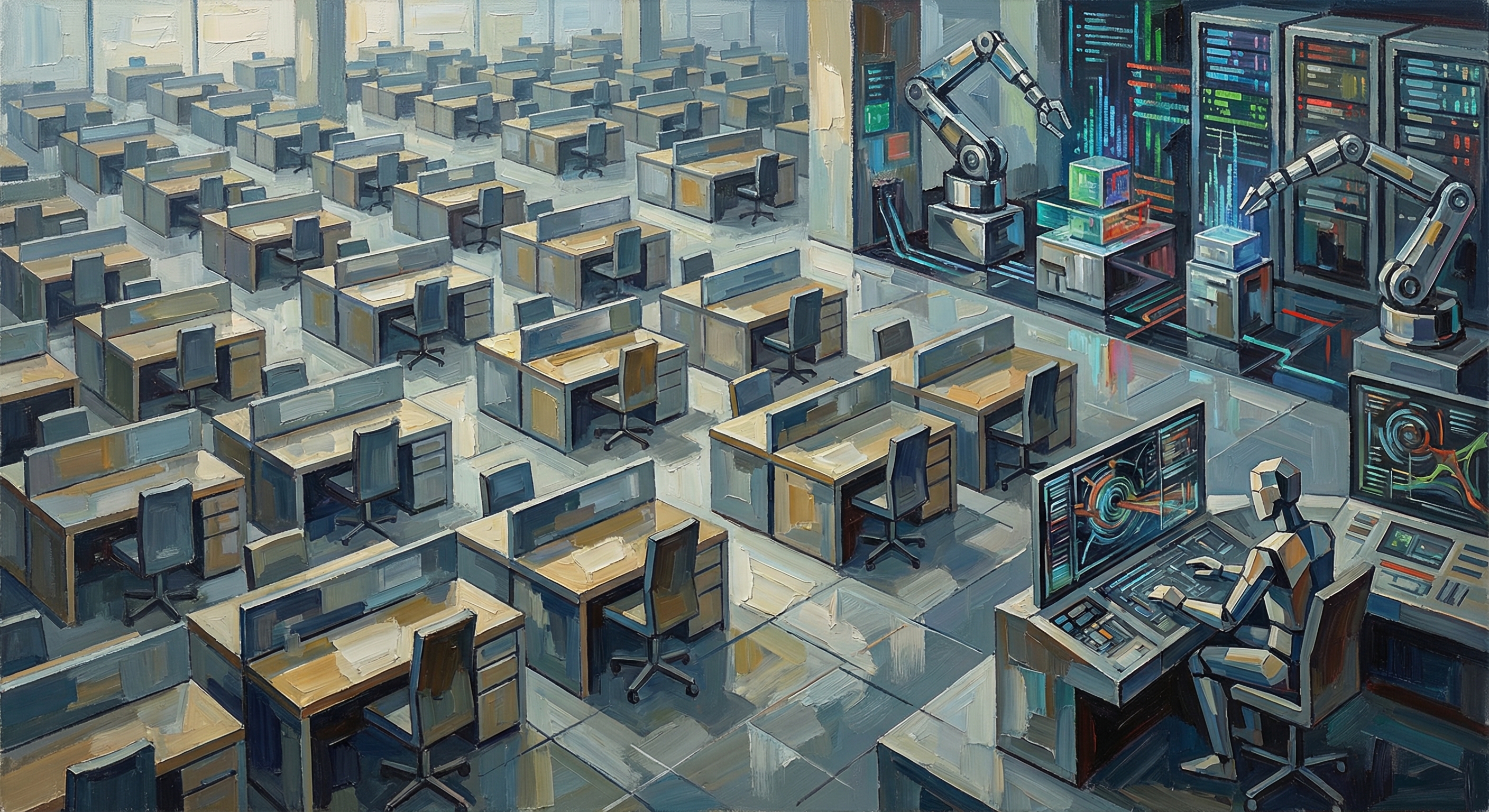

The true existential threat of the AI moment lies closer to home, embedded in the very nature of the technology we are racing to develop. We face a profound structural shift in the economics of production, a transition that capitalist societies are woefully unprepared for. We are entering an era where the firm that once required 100 employees to generate significant value will soon require only five, leveraged by algorithmic power.

This is not merely an efficiency gain; it is a potential demolition of consumer capacity. If the majority of the workforce is decoupled from the primary engines of wealth creation, a critical question arises: Who will purchase the abundance these automated systems produce? We risk facing a paradox of plenty: soaring productivity alongside a drastic contraction of aggregate demand. This will manifest not just as a labor crisis, but as severe GDP downsizing for capitalist societies.

We must recall the fundamental telos—the ultimate aim—of the State: the well-being of its citizenry. It is worth remembering that during the Cold War, the West demonstrated that robust social welfare was not the antithesis of capitalism, but its necessary stabilizer. Proving that a free market system could provide a superior quality of life for the average worker was, in part, how the ideological battle against the Soviet Union was eventually won.

Today, we require what might be called an "upstream mindset." Rather than merely performing downstream heroics—donating vast sums of philanthropy to patch social wounds after the damage is done—we must engineer systemic resilience before the crisis hits.

Paradoxically, the West possesses a critical advantage it currently underutilizes against China: high GDP per capita. This aggregate wealth is a potent lever for a new era of innovation. If great breakthroughs will increasingly stem from hyper-empowered teams of five rather than sprawling industrial behemoths of hundreds, then ensuring more individuals have the resources to dedicate to their own projects becomes economically vital. By securing the material baseline of the citizenry, we add an algebraic leverage to our creative potential—doubling down on innovation by a squared factor.

This demands a radical re-conception of welfare for the algorithmic age. Contemporary well-being must mean more than just a subsistence paycheck at the end of the month. It requires a guarantee of foundational stability—state-supported high-quality residential programs and guaranteed nutrition—that frees the individual from existential anxiety.

We must envision new work relations where being demonstrably productive in one’s own affairs—not mere idleness—unlocks further state funds. Imagine public grants, perhaps guided by AI analysis of viability, designed to bridge the gap between an individual's initial idea and market profitability. This is the infrastructure necessary to enable a revised "American Dream"—one where the path to success, from buying Nikes to building unicorns, is accessible to those displaced by automation.

The inevitable corollary of this shift is fiscal. Tax contributions must tend to gradually bear more weight on highly automated companies. As payroll expenses vanish and profit margins swell due to AI-driven efficiency, the remaining, concentrated class of stockholders will need to accept this new regulatory framework. It is the necessary price for maintaining a stable society capable of functioning as a consumer base for their products.

The window for preventative action is closing. The remaining agency we possess lies in the franchise. We must vote to influence the architecture of this inevitable future. A substantial baseline income—whether it is €1000 a month or provided through services—can fundamentally alter the trajectory of millions of lives, transforming them from casualties of automation into the architects of the new economy.